When stakeholders don't agree

I recently co-presented on how to run a meeting between UX practitioners and stakeholders that arrives at a list of functional requirements for web content. (See our slide deck for “Turn ‘written by committee’ into a good thing with a user-centered content strategy”.) As a User Experience Librarian, I’m often in these kinds of meetings with colleagues from all over the library. Bringing stakeholders (non-UX colleagues) into the UX process can be a positive and productive way to create new web content.

At the end of the presentation, one attendee asked a very thoughtful question: “Do you have any tips for mediating major differences in opinion among stakeholders, as in two stakeholders who have super-polarized views about the best path forward?”

Anytime you’re attempting to reach a collaborative decision, especially about a user-facing service that the group feels heavily invested in, there’s a chance you might end up at an impasse. This has happened in projects I’ve been involved with, and I’ve found that there are a few things that have worked.

Get more information

If there’s a lot of back-and-forth in the meeting without much forward motion, it might be because there’s a piece of information that’s missing. Sometimes that’s a price quote, and sometimes that’s user research. You can tell if this is the problem when the discussion starts to sound like competing conjectures.

For example, I’ll occasionally be in a conversation like this:

“Users will want to see the full list of textbooks.”

“No, users want to search by instructor’s last name, like at the bookstore.”

“No, users often don’t know their instructor’s last name when they’re at the reference desk.”

The back-and-forth might go on, with conjectures from both sides about what the user knows and wants. At this point, especially if I’m hearing myself making vehement conjectures, I might suggest, “It sounds like we need more user research.” Then we might start organizing a Tiny Café, a low-overhead approach to user research. We might give users a survey or do usability testing on mock-ups. Doing user research helps us bring data to the discussion so we don’t have to rely on conjectures.

Try visual thinking, not just talking out loud

If you’re discussing a process or page layout aloud, there’s a good chance that everyone listening will end up with a different idea of what you mean in their heads. Oral communication isn’t the best way to describe a user journey or user interface, and it can be a recipe for disagreements based on misconceptions.

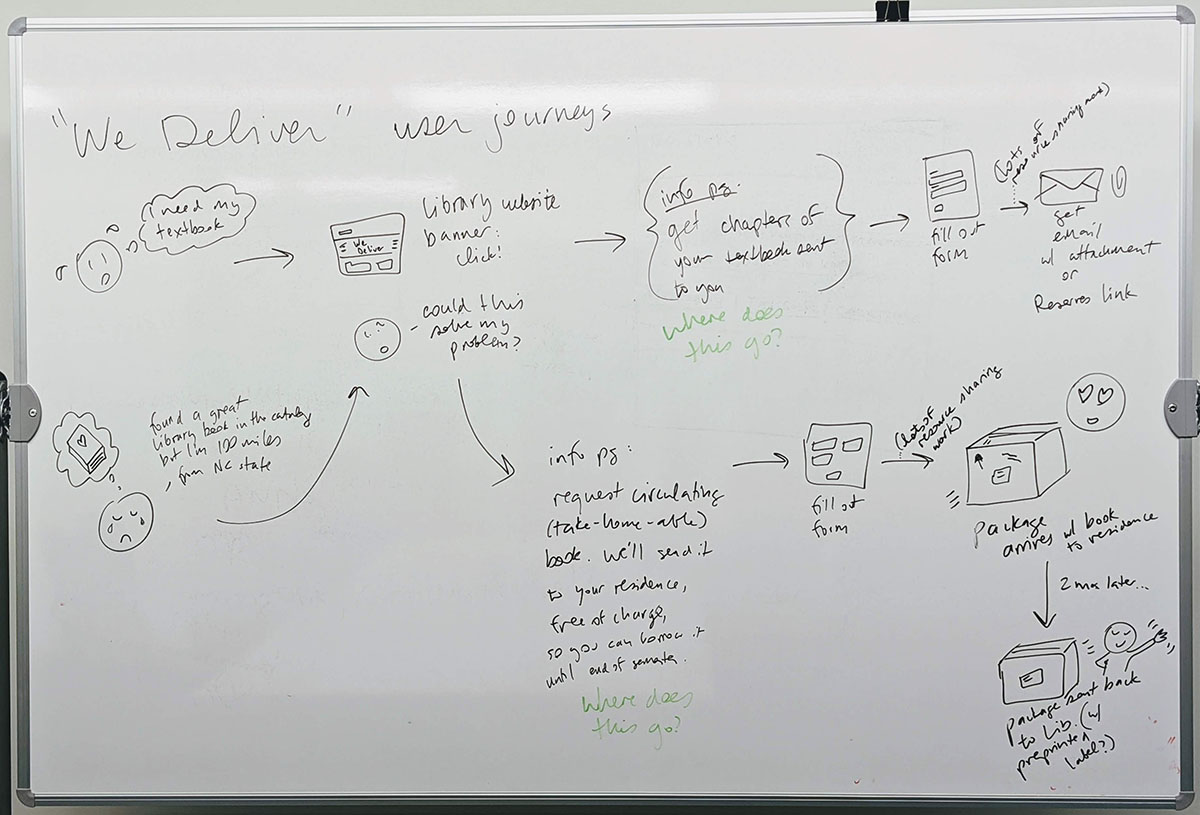

Try visual communication as a way to supplement the discussion. Use a whiteboard and sketch out what you mean, or ask your colleague to. You might end up with a doodle-y flow chart that looks like this:

At this point, the discussion focuses on tweaking the sketch until it looks like what everyone imagined. It also helps the group to identify issues that hadn’t come up in oral discussion. (“Wait, in the second step here, how will the user decide if they need a chapter or the whole book?”) For visual thinkers like me, this approach is highly preferable! I can’t keep a complex process straight if we’re talking about it out loud.

Whiteboarding alternatives for having a visual discussion remotely:

- Sketch your idea on a notepad and hold it up to your webcam. Or have everyone make a sketch, snap a pic, and email it to you

- Create a makeshift document camera by logging into the meeting on your phone, muting it, and angling it at your desk from a nearby stack of books as you sketch

- Use digital tools like Google Slides (my least favorite solution, but it works)

+1 ranking

If you’re at the point of brainstorming with a group, and there are multiple possible solutions, list each option in a Google doc. Dissociate options from the people who suggested them as much as you can: this is about ideas, not personalities. Ask the group to go through the doc and put a +1 next to the options they like.

You might end up with a list like this, taken from a real meeting where we had lots of good ideas but could only dedicate time and effort to some:

Subject specialists show up on relevant searches +1 +1 +1 +1

Tutorials show up on relevant searches

Show relevant items from our collections on workshop pages +1

On pages about tech, spotlight a relevant digital resource/catalog item +1 +1 +1

In the end, you might be able to see that there’s a clear favorite (even if the loudest or most tenacious person in the group has spent a lot of time supporting a different option). The ideas that didn’t get +1’d simply fall by the wayside — quietly, without a negative conversation that might make the suggester feel bad.

Alternatively, after doing this, you might see that the group is split. That could be an indication that you need more information or should make mock-ups of both ideas and test them out.

Use a gradient of agreement

If you’re at the beginning of a project and you can already tell that a group might have strong/conflicting feelings, agree as a group on how you’ll move forward on a decision using a gradient of agreement. The gradient might look like this:

| Endorse | Agree with reservations | Mixed feelings | Disagree but won't veto | Veto |

Using a gradient gives the group more ways to express their thoughts than the yes/no binary. As you’re setting norms for how to make decisions, you might decide as a group to move forward as long as no one is at ‘veto,’ even if there are people at ‘diagree but won’t veto’ (as an example).

I learned about this from a workshop called “Go UX Yourself” (delightful!) led by Amanda VerMeulen at Designing for Digital 2020. Here’s a deeper explanation from TRG if you want the nitty-gritty on this technique.

Wait for someone to retire

I’m kidding (sort of). This is a worst-case scenario.

The techniques of +1 ranking and using a gradient of agreement both depend on strong meeting facilitation skills. It might feel uncomfortable suggesting a different way of running a meeting if you and your colleagues are used to the typical meeting format of oral discussion aided by an agenda. You can set the tone early on by letting your colleagues know what to expect. For instance, in a +1 ranking meeting that I led, the calendar invite read:

We should expect to do some “how might we?” ideation in this meeting for the user needs & features we decided were in-scope and doable at our last meeting. No need to prepare anything beforehand. We’ll do this meeting over Zoom with a kooky Google Doc.

Meeting facilitation is a skill that takes time and lots of emotional labor to learn. You can do it! I hope these techniques help you move forward and get your group on the same page.